Unlike geology or astronomy or biology, which require special places or instruments to examine rocks or stars or micro-organisms, psychological material is all around us. The world is the psychologist’s petri dish. “Why did you take that seat?” I ask my students on the first day of class. Those wishing to hide or escape or show off are soon enlightened, albeit embarrassed, by the revelation that what seems to be the most casual behavior is rife with psychological content.

Prayers often illustrate spiritual meaning far broader than their immediate purpose.

Let this then be my first point of the comparison of psychology with Judaism. Actions are always consequential, abounding with meaning. There is no possibility of escaping one’s moral compass. For example, despite the suspension of everyday activities on Shabbat (Saturday, the Sabbath) there is no “day off” from God’s presence. Prayers often illustrate spiritual meaning far broader than their immediate purpose. Consider the Yismechu (rejoice) part of the Musaf Amidah (a central morning prayer). “Rejoice in the Sabbath” exemplifies the “richness of existence.” The Mi Shebeirach, a prayer asking for healing can be extended to “enable me to sustain myself in this …new job or school or in the military, or new relationship…etc.” Shehechyanu (that we have come to see this day), while recited at the beginning of many holidays is applicable to any celebratory moment: you passed the bar exam or received a text from your long lost friend or convinced your child to clean his room. No holiday or occasion, grand or minor, is needed to demonstrate the presence of Judaism. Like psychology, it is everywhere.

Let this then be my first point of the comparison of psychology with Judaism. Actions are always consequential, abounding with meaning. There is no possibility of escaping one’s moral compass. For example, despite the suspension of everyday activities on Shabbat (Saturday, the Sabbath) there is no “day off” from God’s presence. Prayers often illustrate spiritual meaning far broader than their immediate purpose. Consider the Yismechu (rejoice) part of the Musaf Amidah (a central morning prayer). “Rejoice in the Sabbath” exemplifies the “richness of existence.” The Mi Shebeirach, a prayer asking for healing can be extended to “enable me to sustain myself in this …new job or school or in the military, or new relationship…etc.” Shehechyanu (that we have come to see this day), while recited at the beginning of many holidays is applicable to any celebratory moment: you passed the bar exam or received a text from your long lost friend or convinced your child to clean his room. No holiday or occasion, grand or minor, is needed to demonstrate the presence of Judaism. Like psychology, it is everywhere.

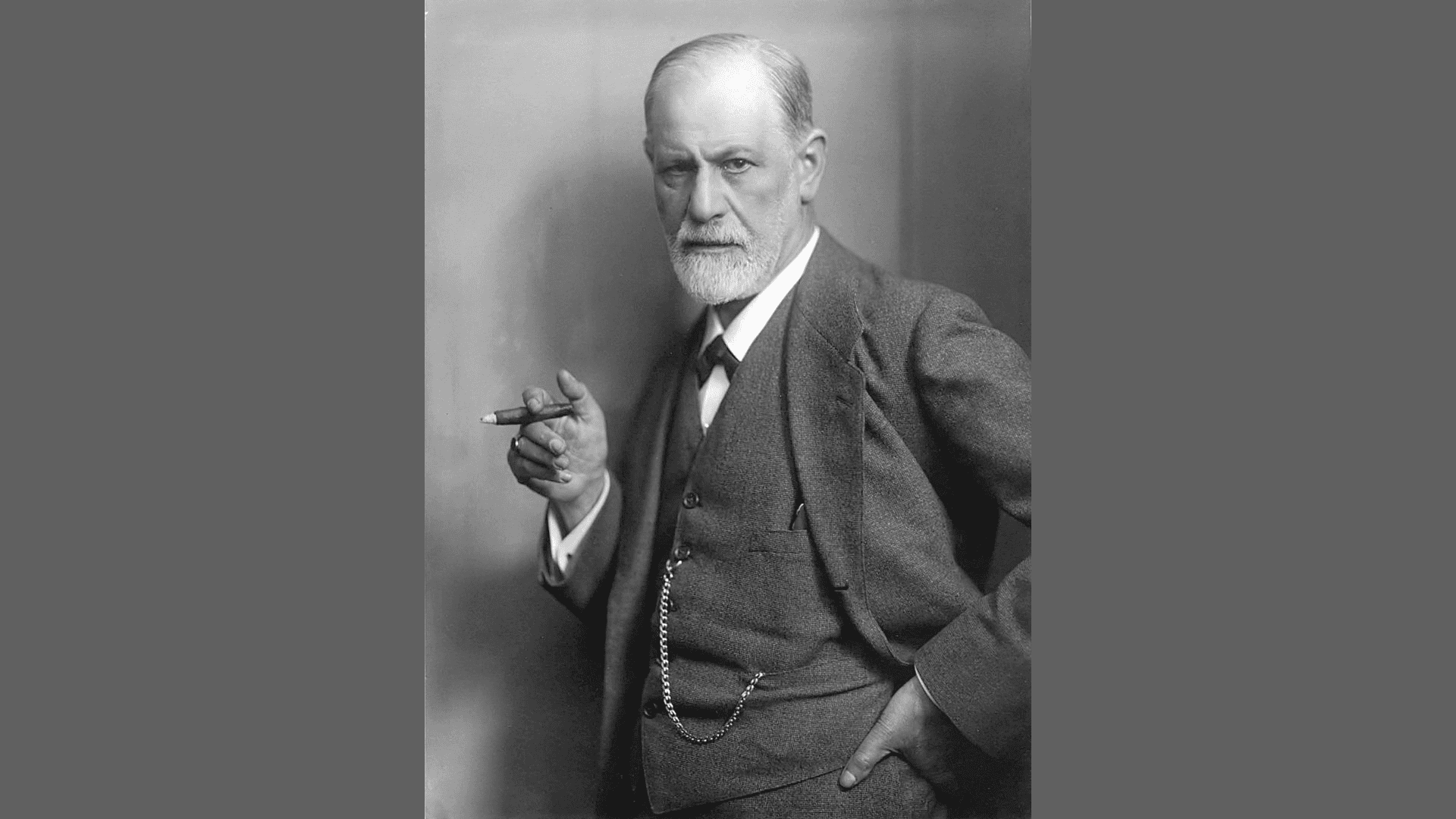

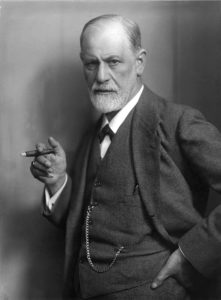

Three specific psychological areas have similarities to Judaism. The first is psychoanalytic theory, the second, therapy, and the third, child development.

According to Freud, understanding personality means understanding motivation, drives largely hidden because they conflict with social norms. Civilization demands behaving for the common good, not acting solely on instinct. Scholars of antiquity believe that religion originated in something similar – the need for social groups to lessen emotional isolation. Freud’s “Civilization and its Discontents” says primitive desires, especially sexual ones, although repressed, are not gone. The newborn, all id, seeks only what it wants, but eventually must develop its superego (the internalized parent) and restrict those wants. Is this not similar to the progressive arc of the stories of the Torah, moving from chaos in Chapter 1 of Genesis, through God’s creation of order, to arrival at the Promised Land in the last chapter of Deuteronomy?

In short, we do not deny our primitive instincts but seek to modulate them. Judaism’s teachings of conquering destructive impulses, e.g. being slow to anger, are lessons we see in Pirkei Avot (Chapters of the Fathers). Leave immediate desires alone and add balance with service to others. Understand what’s hidden in the depths of the soul, entwined in the universal will act on behalf of the community and you shall be rewarded.

While psychoanalysis recognizes many mechanisms that enable us to cope, Judaism too offers its share of defenses. For example, the implicit dialogue between the living and dead serves as proof of the denial of death. The ancient custom of gashing the flesh when in mourning, now altered to tearing the garment, demonstrates both sympathy with the deceased and an attempt to bring the dead closer to the living. The Kaddish (prayer for the dead) recited throughout the period of mourning, and on the anniversary of a death, does not mention death. Praising God when we grieve is a deliberate effort to prevent losing faith. Sublimation is another common defense against a dangerous or primitive feeling by substituting a more socially acceptable behavior. We kick a ball instead of an oppressor. As part of the Jewish New Year ritual, bread, symbolizing sins, is cast into the water. Is not offering up prayer, our words, rather than sacrificing a ram or goat, more humane?

By starting with the idea that nothing is too insignificant for psychoanalytic examination and investigating what usually is identified as the “small stuff.” As Philip Roth’s character exclaimed when his wife sighed in response to his intense anger about burned toast, “life is about toast.” We are immediately led to recognizing how much of Judaism is about the details: Shir HaShirim (Song of Songs), found in Ketuvim, the last section of the Torah, offers specific delineations — the crocus and the lavender, the dove and the swallow – that exemplify the earth’s beauty. On the first day of Sukkot (booths), the fall festival holiday, until the last, we read the Exact Specificity of the burnt offerings and grain offerings: 9 bulls, 7 sheep, 3 goats, one ram, 14 unblemished yearling lambs, two tenths of a gram of flour. Details abound: eleven months of mourning, three steps as one concludes the Amidah, seven repetitions of the concluding prayers ending Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), then three more. Count the number of words in the consecutive lines recited by the Cohanim (priests) 3, 5, 7 – again, precision in numbers. The “Land” is not just a promised, undifferentiated geographic area, but rather a clearly defined region: six cities, three on each side of the Jordan. The daily mitzvoth (good deeds) are specifically 613. How evident it is that God is in the details.

All science believes in the principle of determinism, that any present event is caused by something in the past, that things don’t just happen. To explain a flood, an explosion, or a disease, call on the geologist or the chemist or the biologist. Judaism suggests that if we call the flood or the plague or the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah punishment willed by God, it, too, is an affirmation of the principle of determinism, whether natural or supernatural. Even if, as in Reconstructionism, God is within, rather than beyond nature, he/she/it has produced the present situation. Is not the degree to which generations study Torah evidence of how important Jews deem collective history? Science, religion and psychology are in accord.

And yet, what is psychological therapy but an attempt to change, if not the external, determined world, then the way we individuals look at things or feels about ourselves? A Jew “beats” the chest during the penitential prayer Al Cheyt (because of the sin), an implicit announcement and promise to do things differently, to be better, whether through penitence, prayer or charity, to thus avert whatever fate God might otherwise have decreed.

I also consider the dominant effort of the therapist to be perceiving and interpreting the metaphor, especially to patients who want practical answers. Psychotherapy is not about giving advice or –heaven help us –giving clever homework assignments, but about understanding the metaphor. There may be many interpretations of the same action, yet each evokes a similarity between the inner feeling and the action. Open arms connote openness to hearing new things. How much of Judaism is reliant on this kind of similarity? What do we sing each time we return the Torah to the ark? Etz chiam he (It is a tree of life.) Metaphors in Psalms describe Man or Nature or God: the mountains sing, the islands rejoice. Nature takes on Man’s characteristics, Man takes on Nature’s. Man is clay, a flock, a passing breeze, a bubbling brook; he will flourish like the palm tree and endure like the Cedars of Lebanon. And both Man and Nature will be adorned by God: He is the potter, the shepherd, the rock or fortress or shield. Or, again, Pirkei Avot. Warm yourself at the fire of scholars but beware of being burnt, for they bite like the fox and sting like the scorpion. And Song of Songs—my love is a spray of myrrh, a lily among thorns. roses put on a splendid dress; on the pomegranate’s bough are veils of linen, white and crimson. And throughout the Torah: Moses complains to God about having to carry the burden of his people—like a nurse carrying an infant. “Did I bear this child? he asks.” The message resonates powerfully through metaphor, and, as in psychology, bridges the abyss which often stands between speaker and audience, writer and reader (to keep the metaphors flowing).

Along with this abundance of similarities, we find an emphasis on differences as well. That palm tree grows in the lowest part of the land, the Jericho valley, and the Cedar of Lebanon in the highest; the palm yields this most important of fruits, the date; the cedar has no fruit; the palm loses its leaves, the cedar is evergreen. But both are planted in God’s house, and, for all differences, are united in the kingdom of God.

This combination of making distinctions and finding similarities characterizes our psychological development from childhood forward. Why are we often attracted to that father (or mother) figure? Because of the Oedipal crisis during which we must learn (to our regret) that a mother is not a wife, that a son is not a husband, despite the love of our parents. In developing cognitively, similarities and differences are critical to learning. The young child must learn the difference between water and bleach, between a knife and a spoon, between the sidewalk and the gutter, although they are similar.

In a sense, Judaism is all about making distinctions. The Havdalah (separation) ceremony at the close of the Sabbath emphasizes the difference between the work week and the rest day, or the degree of holiness between the holidays and the Sabbath or, through God’s selection, between the Israelites and the people of the world. In discussing whether punishment is appropriate for those who are responsible for another’s death (be the instrument made of iron or stone or wood) a distinction, the intent, must be considered. As with most modern law, there’s a difference between murder and negligence, despite the same result.

Attending, again, to the metaphor of the palm and cedar trees, so the child also grows to learn that, despite their differences, objects can be grouped together. Who says you can’t compare apples and oranges? They have similar functions as well as shapes. Piaget’s work with children often involved sorting objects of different dimensions to see if they could discover multiple classifications. So, is a blue triangle similar to or different from a blue square? If one has advanced to a higher cognitive level, the answer is obviously both. Alike, if classifying by color; different, if by shape.

Comparing each Torah portion with its accompanying Haftorah (prophetic reading), we note that the relationship can be based on similarity or difference. On Tisha b’av (ninth day of the Hebrew month of Av), the Torah readings recall the Temple’s destruction and the Haftorah is ablaze with Jeremiah’s predictions of doom: the fig tree will not bud and the sheep will vanish. Another connection of similarity, and there are many, is the reading in Shamot (names). In the Parashah (portion) Moses follows God’s guidance to go and speak to his followers for He will be with him. And in the Haftorah (Sephardic) we read of Jeremiah’s calling the people to God’s word. But in Vayera (and he appeared), readers learn of the proposed destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah while the Haftorah narrative tells tales of rescuing one barren woman, Hannah, to have a child and another, a widow in debt, whose jars of oil allow her to repay debts and keep her sons from slavery. Destruction and rebirth, a significant contrast. In Tzav (command) the Torah consists of details of sacrifice while the Haftorah speaks of acts of love instead of sacrifice. What better index of this complexity than the holiday of Simchat Torah (rejoice with Torah): the reading begins with the last book of Moses, followed by the Haftorah about his successor Joshua, similar but different leaders, as will be seen throughout the coming Books.

Akin to that major task for the developing child–responding to the similarities or differences among objects–is the major question facing today’s Jew: How much of the past to keep and how much to change? Does recognizing the importance of tradition, performing tasks similarly, make one out of step with modern-day science or practice? This is an age-old question. And if I change, agreeing with what Samuel Johnson called “the most important act of civilized life, making distinctions,” does that make me an unappreciative child of my forebears? Does knowing one’s people’s history liberate or confine me?

Ethan Gologor has been a NYS licensed psychologist for almost a half centurY. He received his Ph.D. from the New School for Social Research and is currently the Dean of Liberal Arts at Medgar Evers College of CUNY (City University of New York). He is the author of “Psychodynamic Tennis” and “Today I am a Runner.”