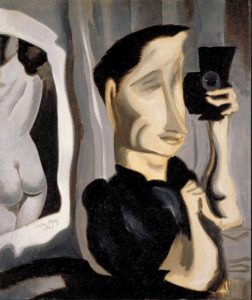

Self-Portrait with Gun (1932) WikiArt

Born Emmanuel Radnitzky, Man Ray was a constantly exposed, constantly hidden artist of the dada (nonsense of the everyday) avant garde tradition. Painter, photographer, film-maker, Surrealist, and object-maker, he was one of America’s – and the world’s – most influential artists. For nearly three quarters of a century, Man Ray, as the New York Times said in 2009, was the “sole American in his avant-garde milieu, a fact that overshadowed his religion and class, and a distinction that he clearly relished.”

Emmanuel Radnitzky was born in Philadelphia in 1890, and moved to Brooklyn, New York as a child. His artistic abilities were evident even during his high school years. He rejected a scholarship to Columbia University School of Architecture in favor of art studies at the Francisco Ferrer Social Center – The Modern School – in Greenwich Village. The Center, says gallerist and scholar Francis Naumann, was home to “art and anarchy in the pre-dada period.” The young artist studied drawing with Robert Henri. By 1912, wary of anti-Semitism, the Radnitzky family left behind their birth name, and Emmanuel fully become Man Ray.

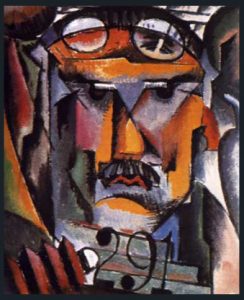

Portrait of Alfred Stieglitz (1913) WikiArt

In 1913, together with poet Alfred Kreymborg, Man Ray attempted to create an artists’ community in Ridgefield, New Jersey. By 1915, he had become involved in the anti-art dada movement, spending time with Alfred Stieglitz at his internationally renowned 291 Gallery. Stieglitz introduced Man Ray to both photography and New York’s artistic society. Man Ray initially intended to photograph and inventory his prolific output of paintings. It was several years before he began to use the camera as an art tool. In 1920, Man Ray was a founder of the Societe Anonyme – one of the first American museums to promote modern art. It, and his first marriage to Adon (Donna) Lacroixe, soon failed, though he and Donna would not divorce until 1937.

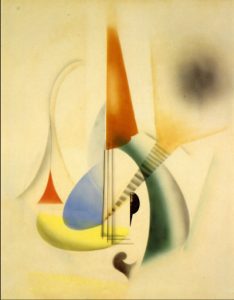

Jazz (1919) WikiArt

Man Ray arrived in Paris in 1921. There he found his artistic and spiritual home. He loved the city and its artists, and the art community welcomed him, beginning what would become a lifelong – albeit interrupted – love affair with the City of Lights. He was perceived neither as Jewish nor “of a certain (working) class,” and gained entry to artistic society.

In 1922, the iconic Rayograph – an innovative photographic process that creates an image by placing objects directly on a sheet of photographic paper and exposing the paper to light without using a camera – became popular. Man Ray’s Les Champs Délicieux (“The Delightful Fields”), a collection of rayographs, was published the same year.

During the 1920’s and 30’s, Man Ray enjoyed success as a fashion and portrait photographer with work appearing in Harper’s Bazaar, Vu, and Vogue. His photography was epitomized by photos such as Le Violon d’Ingres (1924) in which he mixed objects superimposed on portrait images. He created portraits of every possible type of person. “He was part of that world – not a stranger,” Timothy Baum told Jewish Views. Baum was Ray’s closest friend and confidant , despite their 50 year age difference. “We were as close as two friends could be,” he told JV. “Man Ray was a rebel. He did not have to be shy about his great talent. He was a very natural painter. ” Timothy Baum was introduced to JV by Roger Browner, a nephew of Juliet Browner, Man Ray’s widow. Browner is a Trustee of The Man Ray Trust.

“Man Ray was a rebel. He did not have to be shy about his great talent. He was a very natural painter.”

Lee Miller (1930) WikiArt

When the Nazis threatened Paris, Man Ray, an American and a Jew, knew he had to flee. Much of his work was left with his trusted materials supplier. He rolled up an additional group of paintings and attempted to flee with his then girlfriend. As they began their escape, she decided she could not leave her family, so she remained. Man Ray hid a number of his paintings in the walls of his house, and left for America.

Arriving in the United States in 1940, Man Ray worked in Hollywood as a high fashion and celebrity photographer. As an artist, he could gain little traction on the American art scene. In 1946, he married Juliet Browner in a double wedding shared with Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning. In 1951, the couple returned to Paris.

Upon their return, Man Ray and Juliet’s home – and his studio – were in a structure built directly on the cobblestones of a Paris street – there was no foundation, no substantial flooring, and no heat. The space – actually a garage with a loft – was between two houses. Electricity came from a neighbor’s house. “It still looked like a garage,” commented Timothy Baum.

The artist’s friends were especially concerned about the danger posed by the coal stove used to minimally warm the sleeping area and the bathroom. Only in the last years of his life did he and Juliet buy an apartment near the Jardin du Luxembourg area on the left bank of the Seine.

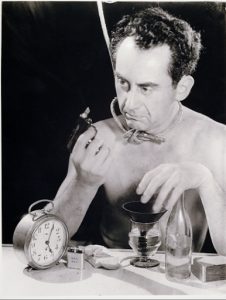

Self Portrait (1941) WikiArt

“He did not miss America,”says Timothy Baum. “He felt ‘the artist’ was not given enough respect.” He returned to the States only two or three times, although “he did stay in contact with his family,” says Baum, noting that his brother, Sam, also lived in Paris.

“Man Ray told me ‘the biggest obstacle to his painting career was that he had become too good a photographer,” says his friend Baum. He had enjoyed being a painter from childhood and, on his passport, had listed painter, not artist, as his profession. As a result, when he reached the age of retirement, Man Ray received a letter from the French government inviting him to discuss his pension. The French government had him registered as a house painter. Accordingly, he received a retiree’s pension for the remainder of his life.

Baum told JV that Man Ray also had a close relationship with his niece, Naomi Savage, a well recognized American photographer. “She appears to be the only relative with whom he had a real affiliation – other than his wife.” Man Ray and Juliet had no children. She was heir, and when she – Juliet – died in 1991, her brothers and Naomi were the main inheritors of his legacy and estate. The Browner family continues to administer The Man Ray Trust.

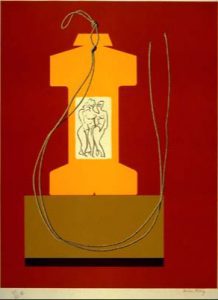

Untitled (The Three Graces) (1969) WikiArt

Roger Browner, Juliet’s nephew, the son of Eric Browner, Juliet’s brother, is a Trustee of the institution.

“The marriage of Man Ray and Juliet,” says Baum “was a true love affair.” “She adored him and he adored her – they were very compatible. Unlike so many in that world – a movie star kind of world – he was faithful from the day he met her until the day he died.” Baum noted that when Man Ray said he wanted to give up photography to paint, she supported his decision.

Man Ray was far from the struggling artist. When he did sell a photograph or a painting, “in a very nice way, he said he preferred cash – but, of course, would accept payment in any currency. The rumour that a million dollars was hidden in his studio,” says Baum, “is not correct. But he did have about a million in cash in secret bank accounts.”

“I met Man Ray in Paris,” recalls Janet Lehr, a renowned dealer in photographic art. In 1972, she recalls, “considering photography as ‘art’ was an outrageous statement.” She was then developing the American Photography Collection for the Bibliotheque Nationale de France (BN), and was introduced to Man Ray by the institution’s Print and Photography Director, Jean Adhemar. “Man Ray was most anxious to welcome me to his home. In 1976, when he died, I had just completed the BN American Photography Collection. I met with Man Ray on each of my trips to Paris. On each trip I attempted to buy photographs from him.”

Portrait of Juliet (?) WikiArt

“My overriding impression of Man Ray was that he was a broken man – as much an emotional victim of the Holocaust as any survivor,” added Lehr. “He was traumatized, indeed, a victim of the war. At times he would sell his work – always asking for payment in cash. Sometimes he was unwilling to sell anything. He behaved as though he were shell-shocked. His home was a squatter’s hovel with carpet covering a cobble stone ‘floor’. The main room was lined with drawers full of photographs.”

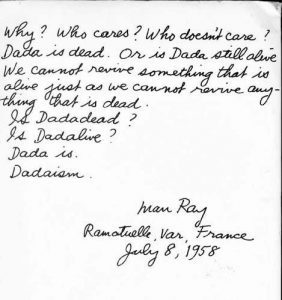

Man Ray was notoriously secretive. “We never discussed his mind-shattering war time ‘chapter’ – suddenly finding himself an artistic ‘nobody’ in America, after having been the toast of Paris. The man I met, got to know, and bought art from, was a broken soul. Although he had escaped and spent the war years in California, World War II took its toll on Man Ray. As an artist, he no longer believed that dada was relevant. He gave me the following note he had written in 1958:”

Lehr shared more musings on their time together: “We met every three months from 1972 until his death in 1976. Our quarterly meetings began with lunch, always in the comfort of a warm restaurant. In his home, there was a noticeable chill in the air. Only a simple table decorated the dimly lit entry. The rooms were ringed with files. Beneath the modest floor coverings were cobblestones. I feared the front door could easily have been pushed and wondered ‘did the artist even use a key?’ The bone-chilling feeling I got from Man Ray and his surroundings of poverty was pure and continual fear.”

Lehr shared more musings on their time together: “We met every three months from 1972 until his death in 1976. Our quarterly meetings began with lunch, always in the comfort of a warm restaurant. In his home, there was a noticeable chill in the air. Only a simple table decorated the dimly lit entry. The rooms were ringed with files. Beneath the modest floor coverings were cobblestones. I feared the front door could easily have been pushed and wondered ‘did the artist even use a key?’ The bone-chilling feeling I got from Man Ray and his surroundings of poverty was pure and continual fear.”

“I shouldn’t call it fear,” commented Timothy Baum. “I would call it wariness. For example, in 1965, after Man Ray had his Los Angeles retrospective, he sent many of the works to his niece, Naomi, rather than sending them back to France. He saw it as a kind of insurance in case Communism took over France. She ended up keeping the pieces, despite claims by the Browner Family that she ‘had more than she was supposed to have.’ The family tried to reclaim the works: they wanted as much as they could get,” Baum told JV. “They did not win.”

Lehr recalled that “at one of our quarterly meetings, my late husband accompanied us. After lunch, we came back to the studio and he was seated in the entry hall, patiently waiting, shivering even in his overcoat. Man Ray and I were focused, working, and didn’t notice the temperature. When we left, my husband succinctly asked, ‘Are you crazy? It’s freezing.’ Needless to say, Louis never joined us again.”

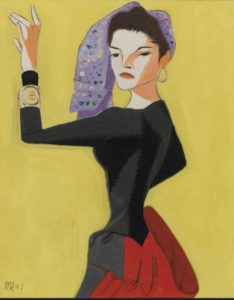

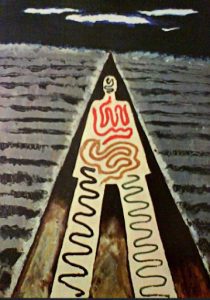

A Night at Saint Jean (?), WikiArt

“I always wondered about those cobblestones,” Lehr reminisced. “Had Man Ray’s home been built directly on the street?” (It was.) “I can still feel those stones. I remember, too, those times when I would come to buy, but Man Ray was not interested in selling anything! I’d leave, quite disappointed.”

How much were Man Ray’s life, work, and secrecy influenced by his Jewish, first-generation-in-American experience? Throughout his life, the former Mr. Radnitzky sought to conceal and assimilate. As noted in the New York Times review of the Jewish Museum of New York’s 2009 multimedia retrospective, Alias Man Ray: The Art of Reinvention, “early in his career, Fascism was on the rise, and Jewish artists were routinely ghettoized…(Ray) made a sport of trying to conceal his background, even late in life when he had achieved artistic recognition.”

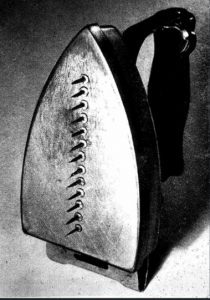

Despite Man Ray’s conscious attempts to create himself apart from Emmanuel Radnitzky, references to his past are visible in his work. For example, The Gift, an early “ready made” sculpture created (and photographed) on the afternoon of the opening of his first Paris show, was comprised of fourteen thumbtacks glued to an iron. His choice of material for this piece of Dada art, elicits questions: is it a reference to his heritage – presenting the tools of his tailor father and seamstress mother’s re-imagined in the context of the absurd and surrealism? New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) called it a “menacing blend of domesticity and sadomasochism.” The piece disappeared from the gallery during opening night. Authorized replica editions were made in 1958 and then in 1972 as part of Galleria Il Fauna’s “edition of eleven” – a display using different types of inter-war irons.

The Gift (1921) WikiArt

Man Ray died in Paris in November 1976 from a lung infection. He was interred in the Cimetière du Montparnasse in Paris. His epitaph reads “unconcerned, but not indifferent.” Juliet Browner died in 1991, interred in the same tomb. Her epitaph reads “together again.”

“Although assimilated,” Timothy Baum recalled, “Man Ray was respectful of the Jewish religion, had been a Bar Mitzvah, and married an Eastern European Jewish woman. He never denied his heritage.”